The First Great Masters Track Meet, by Roger Robinson

Imagine a track meet with Peter Snell, Jack Foster, Harold Nelson, Roy Williams, and Jeff Julian (all New Zealand), Chris Brasher (GB), Maeve Kyle (Ireland), and Albie Thomas, Dave Power, and Pat Clohessy (all Australia), all in action: that’s four Olympic gold medals, three Commonwealth golds, and ten others, Olympic, Commonwealth and European, plus a Fukuoka Marathon winner, creator of the London Marathon, and three great coaches. All competing, all in the same two-day meet. How?

It happened fifty years ago, 21-22 January 1974, when the Canterbury Veterans Athletics Association had the inspired idea of putting on a two-day international masters meet immediately before the Christchurch Commonwealth Games. Bill Rollo was chair of the committee, and George Currie secretary/treasurer. It was probably only the second all-masters track meet in world history, after David Pain put on the first US Masters Track and Field Championship in San Diego in 1968. The first New Zealand championships and first World Championships came a year later, 1975.

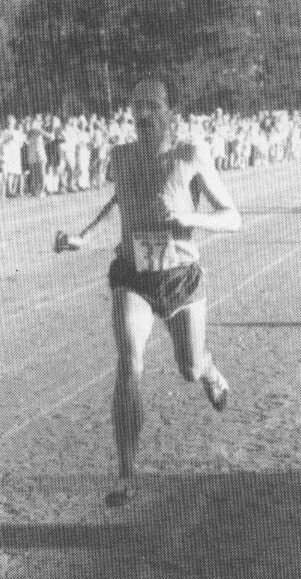

The great boom in masters running and athletics began about then, and it’s no fantasy to say that the Canterbury meeting helped light the fuse. It was conducted as a serious track meeting, worthy of its timing just before one of the best track meets of all time. Two world records showed what older athletes can do, Maeve Kyle’s 62.0 W35 400m, and Jack Foster’s epic 29:38.0 M40 10,000m. The decaying cinder track at Rawhiti Domain, New Brighton, was a come-down from the shiny new all-weather Games track at Queen Elizabeth II Stadium, but the committee made the best of it.

Foster was never a man to make a fuss. He could win in mud if he had to, and often did. He was the only competitor in the masters’ meet who also had a place in the Games themselves, and made good use of his sharpening race at Rawhiti when he won his legendary silver medal in the marathon nine days later.

Snell won the M35 100m (11.7) and 400m (51.5). It was basically show-up-and-run, and the always reticent Snell had to identify himself twice as they wrote names down before the 100m start.

“My, how times change,” commented masters official and pioneer Clarrie Gordon, according to a brief story in “The Press.” The world thought Snell was warming up for the task of carrying the Games baton on its acclaimed lap at the Opening Ceremony two days later, but the world was to get a surprise – see my next post.

Several who became leaders in New Zealand masters athletics had their first international wins that day, including throwers Sam Johnson, Dave Leech, and Arthur Grayburn. Aussie competitor Wal Sheppard became a major driver in the development of world masters athletics. Many competitors had roles in the main Games, including Snell on the Jury of Appeal, Brasher writing for the Observer, Clohessy as Aussie coach, and M50 javelin winner Gideon Tait heading Games security, once he put his Assistant Police Commissioner hat back on.

Christchurch was in the mood for athletics. The people didn’t mind the modest venue. More than two thousand showed up each day. Look at the crowd in the historic photo of Foster (from History of New Zealand Veteran Athletics 1962-1999). Repeat: four thousand attended to watch masters track and field. That meet deserves a higher place in our sports history.

Roger Robinson’s chapter on the 1974 Christchurch Commonwealth Games is in his book, When Running Made History (Canterbury University Press, 2019), called “the best running book ever published” (Amby Burfoot, Runner’s World).

Photo credited to the History of NZ Vets Athletics – Jack Foster racing at Rawhiti.